In 1954, the Supreme Court reached a historic decision in the case of Brown v. The Board of Education. The courts overturned the previous ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In Plessy v. Ferguson, it had been decided that segregation was constitutional, as long as both sides received equal treatment, hence the phrase “Separate but Equal.” With the new ruling in Brown v. The Board of Education, this separate but equal ruling was deemed unconstitutional as it applied to schools. Thus, the courts ruled that the nations’ schools must desegregate.

In 1954, Greensboro became the first city in the South to announce its planned compliance with the Supreme Court’s ruling. In actuality, desegregation was not enacted in Greensboro until 1971 (seventeen years later), making it one of the last cities in the South to end segregation of public schools. From 1955 until 1967, many of North Carolina’s school districts, including Greensboro’s avoided real desegregation by consenting to token desegregation and enacting illusive “freedom of choice” and pupil assignment plans. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed “freedom of choice” plans across the South, and in 1970, a federal court ordered Greensboro’s schools to finally desegregate. By that time a new progressive leadership on the school board and the Chamber of Commerce, led by former Greensboro College trustee Al Lineberry, Sr., pledged to not only abide by the court ruling, but use school desegregation as a means for a more genuine racial reconciliation in Greensboro.

Meanwhile, at J.C. Price School in the late 1960s, the administration had been aware of the ongoing struggle between segregationalists and those striving for integration. They were also aware that, sooner or later, segregation would end. That being said, a specific date was never given as to when the integration would happen.

Melvin Swann – 28 minutes 18 seconds

When the city schools finally began desegregating in 1971, the teachers and faculty had no prior warning to its arrival. Teachers and faculty learned from the news stations that segregation had ended. They arrived at school the next day fearing for their employment. Principal Melvin Swann had to rush to the city superintendent’s office to ensure that his teachers were indeed still going to have their jobs. The majority of them did get to keep their jobs, but quite a few teachers ended up with administrative jobs at other schools. The Peeler-Swann Family Association, a group of Price alumni and former teachers which meets annually, was formed in 1971 to keep memories of Price School alive.

When desegregation took effect, the students of J.C. Price School were bused to other schools in Greensboro because the city’s integration plan called for a 70/30 ratio of white to black students in all public schools. Price School also went from being a junior high school to an elementary school, a transition most Price alumni and teachers viewed as a demotion. Because a large majority of black students lived in all black communities, children had to be bused to other schools to make this ratio a possibility. This model for desegregation was a joint plan made first by the City of Greensboro, then revised and edited by the NAACP.

While the integration of Greensboro’s schools was relatively smooth and was seen a success by those who had been struggling against segregation in schools for decades, there was some opposition from within black Greensboro to the 1971 desegregation plan. The older generation of black leaders were relatively committed to desegregation under the terms largely dictated by the white school board. Younger black leaders, especially Nelson Johnson, were concerned that it was desegregation in one direction, black students into white schools, and that only black schools would be closed and only black teachers would be fired. There was even an initial plan to close Dudley High School and Price, but black protest got that rejected.

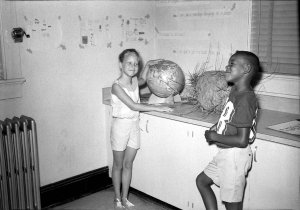

Courtesy of the Greensboro Historical Museum

“The world is a hornet’s nest except for children.”

Black and white students at J.C. Price School after 1971.

While the integration of public schools was a tremendous success for the civil rights movement, there were consequences, especially for the Warnersville community. With a percentage of the Warnersville children now being bused to different schools away from the neighborhood, the cohesiveness of the Warnersville community suffered. No longer were “local” teachers necessarily teaching the children. Instead, the students were being taught by unknown teachers who did not share the emotional attachment to Warnersville which had for so long been a mainstay of the J.C. Price teachers. Lack of teacher involvement within the Warnersville community, in addition to a relaxing of disciplinary standards, was seen as having a negative impact on both the welfare of the children and the community.

Lewis Brandon – 2 minutes 5 seconds